15

NAMĀZ DURING TRAVELS

Being Safarī or Musāfir means being a traveller. If a person

intends to go to a place that would take three days by the short days of year

by walking or by riding a camel during the short days of the year, he becomes a

musāfir as soon as he reaches beyond the last houses of the place he lives in

or on one or both sides of his way. If he passes by the last house without

intending to go to a place that is three days way, he does not become a

musāfir even if he travels all over the world. An example of this is the case

of soldiers searching for the enemy. But he will become a musāfir on his way

back. If a person who has started off with the intention of going to a place

that is two days way, intends on the way or after reaching the place to go to

another place which is two days way from his first destination, he does not

become a musāfir when he is on the way to the place which is four days way.

While leaving ones temporary home with the intention of going three days way,

one becomes musāfir as soon as one passes beyond the last houses on both sides

on ones way. Yet the last house does not have to be out of sight. One does not

have to have reached beyond the houses that are only on one side of the way.

Nomads camping at the seaside or near a forest become musāfir when they leave

their tents. A person who lives in a city must have passed beyond the houses

outside the city as well as the houses adjacent to the city and the villages

where rows of houses from the city reach. It is not necessary to have gone

beyond empty fields or vegetable gardens adjacent to the city. Even if there

are farmers or watchmens houses in the fields or vegetable gardens, they or

the villages beyond them are not counted as parts of the city. In empty fields,

those large cemeteries that are close to town are called Finā. Grounds which the townsfolk use for

threshing grain, for horse-riding, for diversion, and parts of a lake or sea

which they use for hunting etc., [factory buildings, schools, and barracks] are

counted as part of the town. That is, they must be passed. If a finā is more

than two hundred metres away from the town or if there is a field between them,

it is not a part of the town. But it is sahīh to perform the prayers of Friday

and Iyd at a finā that is far away. Villages, cities in between which and the

city is a finā are not counted as parts of the city. It is not necessary to

pass beyond such villages. One becomes safarī when one reaches beyond the finā

only. With large cities, a finā is stil

counted as a part of the town when it is more than

two hundred metres from the town. It is written in Imdāds

commentary titled Tahtāwī that according

to a narration called Mukhtār, even if there are houses or a finā in between,

having gone beyond the villages is not a condition.

It is not a condition that one will walk all the time until evening. On

a short day, it will be sufficient if one walks from the time of morning prayer

until the time of the early afternoon prayer. This journey is called, merhala,

manzīl, or qonaq (stage). It is also

permissible for one to rest in the meantime. Even one goes on a journey of

three days on a fast vehicle, such as a train, one still becomes musāfir. [Majalla[1], 1664] If there are two ways of going to a place,

one of the ways being shorter than the other, the person who goes the shorter

way does not become a musāfir. If the longer way takes three days by walking, a

person who goes by that way on any vehicle becomes a musāfir.

Ibn-i Ābidīn says: All ulamā have

described the way of three days by a unit called farsāh,

the distance travelled in one hour. Some of them said a way of three days was

21 farsāhs; some said it was 18 farsāhs; and others said it was 15 farsāhs. The

fatwā has been given according to the second judgement. In the fatwā of the

majority, one marhāla, the distance travelled in one day, is six farsāhs on a

smooth route. One farsāh is equal to

---------------------------------

[1] A world-famous book on Islamic jurisdiction written by Ahmad

Jawdat Pāsha 'rahmatullāhi ta'ālā 'alaih', (1238 [1823 A.D.], Lowicz -1312 [1894],

minute, which is equal to

In the sea, the speed of a sailing-boat that sails in weather with a

medium wind is essential. Accordingly, a person who goes to Mudanya from

Istanbul does not become safarī. But a person who goes from Istanbul to Bursa

becomes safarī. One who flies on a plane is supposed to have gone on the road

or sea below the plane. For today, one who starts on a journey by bus from the

quarters named Fatih,

---------------------------------

[1] Written by Abdullah bin 'Abd-ur-Rahmān

'rahmatullāhi taālā 'alaih'.

[2] The book Mir'āt-ul-Harameyn, written in Turkish by Eyyūb Sabri Pāsha 'rahmatullāhi ta'ālā 'alaih', (d. 1308 [1890],) consists of five volumes. The quotation above is from the Medīna section of the book.

Aksaray and Üsküdar in Istanbul, becomes safarī

when he reaches beyond Edirnekapż cemetery, Topkapż cemetery or, if he follows

the way on the sea-shore, the cloth-factory in Zeytinburnu, and the place

between the great military building named Selimiye Kżžlasż and Karaca Ahmed

cemetery, respectively.

Performing two rakats of those prayers of fard

namāz that contain four rakats is wājib for a safarī person in the Hanafī

Madhhab, sunnat-i-muakkada in Mālikī, and preferrable in Shāfiī. Following a

settled[1] imām is permissible when making adā according to

the Hanafī Madhhab, permissible both when making adā and when making qadā

according to the Shāfiī Madhhab, and mekrūh in either case according to the

Mālikī Madhhab. It is explained in the previous chapter how a person performs

namāz behind a settled imām. For three days plus three nights, he can make

masah on his mests. He can break his fast. It is not wājib for him to perform

the Qurbān. If a musāfir is comfortable enough, he should not break his fast.

Even a person who sets out on a journey for sinful purposes becomes a musāfir.

Anybody, whether settled or a musāfir (travelling), whether with an

excuse or not, may perform a supererogatory namāz while sitting on the back of

an animal as it walks as well as when it stands still while being outside a town.

The sunnats that are before and after the five daily prayers of fard namāz are

supererogatory. Only the sunnat of the morning prayer is not supererogatory.

Though it is very good to put the hands under the navel with the right hand

clasping on the left when saying the Fātiha and the other sūras, they might as

well be put on the thighs. Any kind of sitting posture is permissible. No one

is permitted to perform namāz while he himself is walking; walking nullifies

namāz [Jawhara]. See chapter 19! He can

perform namāz in that manner as he goes through the cities on his way. But it

is mekrūh for him to perform it in that manner in his hometown. He bends for

the rukū and makes the sajda by signs. He does not put his head on something.

It is not

---------------------------------

[1] 'Muqīm' means 'settled', 'not safarī'.

necessary to turn towards the qibla when beginning

or while performing namāz. He has to perform it in the direction towards which

the animal is walking. Even if there is a great deal of najāsat on the animal

or on its halter or saddle, the namāz will be acceptable. Yet it will not be

acceptable if he sits on the place smeared with the najāsat. Also, it is

necessary to take off the shoes if they are najs. His controlling the animal

with small movements such as spurring it with his feet or by pulling its reins

does not nullify the namāz. It is permissible for a person who has begun his

supererogatory namāz on an animal to dismount quickly and finish the namāz on

the ground. Yet it is not permissible to begin it on the ground and finish it

on the animal.

It is not permissible to perform a namāz that is fard or wājib on an

animal unless there is darūrat. The book Halabī

says: The conditions for performing the fard prayers on an animal are the same

as those for performing the sunnats. Yet it is permissible only when the

excuses pertaining to the tayammum are present. Hence it is understood that

when you are settled or travelling you can perform the fard prayers on an

animal outside of town when there is a good excuse for doing so. Examples of

good exuses are when your property, your life, or your animal is in danger. A

little mud does not suffice for an excuse. It becomes an excuse when it is deep

enough for your face to go in and become covered. A person without an animal

performs namāz standing and by making signs when there is a great deal of mud.

The Imāmayn said that if a person who cannot mount an animal has someone to

help him, this last excuse will no longer be valid. When performing a namāz

that is fard or wājib, it is necessary to get the animal to turn towards the

qibla. If one cannot manage it, one must do ones best at least.

If a musāfir, that is, a traveller, expects that his excuse will be

gone towards the end of the prayer time, he had better wait and perform his

namāz

on the ground; however, it is still permissible

for him to perform it on the animal as well. Likewise, a person who expects to

find water is permitted to perform namāz at its early time by making a

tayammum. Performing namāz on the two chests called Mahmil

that are on an aminal is like performing it on the animal itself. A person who

is able to dismount cannot perform the fard namāz on a mahmil. If the legs of

the mahmil are lowered down to the ground, it serves as a divan. At this point

it becomes permissible for one to perform the fard while standing on it. But

one cannot perform it while sitting.

Since a two-wheeled cart cannot remain level on the ground unless it is

tied to an animal, it is like an animal both when moving and when still. Any

carriage with three or four wheels that can remain level [such as a bus, a

train] is like a divan, if it is not in motion. It is permissible to perform

the fard namāz standing on it. If the carriage is moving it is like an animal.

It is not permissible to perform the fard on it without a good excuse. You must

stop it and perform namāz standing towards the qibla. [If you cannot stop it,

or if you are on a vehicle which you ride by paying some fare, you get off at a

convenient place. If the vehicle leaves you, take the next one or another

vehicle that starts from that town. When getting on the first vehicle you

should negotiate accordingly. If this is not possible, either, it is

permissible to perform namāz by making signs sitting, as you would do in namāz,

and you must turn towards the qibla as well as possible.]

It is not permissible for an ill or travelling person to perform the

fard namāz by signs while sitting on a divan or in a chair with his legs

hanging down. An ill person should perform his namāz on the floor or on a divān

moving in the direction of qibla turning himself towards the qibla. See chapter

23. It is better for a person who is safarī to imitate the other three Madhhabs

and perform the early and late afternoon prayers together and the evening and

night prayers together, standing towards the qibla when the vehicle stops on

the way. According to the Mālikī and Shāfiī Madhhabs, in a safar that is not

sinful and which is a distance of more than eighty kilometres, taqdīm, which

means to perform late afternoon prayer right after early afternoon prayer in

the time of early afternoon prayer or to perform night prayer immediately after

evening prayer in the time of evening prayer, and tehīr, which means to

postpone early afternoon prayer till the time of late afternoon prayer and

perform them together or to perform evening and night prayers likewise, are

permissible.

This practice is not permissible before one starts

ones journey. A place where one intends to stay for less than four days

becomes a safarī place. When at a place of this sort, one can make qasr

(performing early and late afternoon prayers together), or jam (performing

evening and night prayers together) in case of haraj. Making taqdīm in jamāat

in a mosque on account of rain is permissible, yet there are seven conditions to

be fulfilled. There is no unanimity among scholars as to whether it is

permissible for an ill person to make jam. [To imitate another Madhhab does

not mean to change your Madhhab. A Hanafī person who imitates Imām-i Shāfiī

(rahmatullāhi taālā alaih) does not leave the Hanafī Madhhab]. It is stated

in the fatwā of Shamsuddīn Muhammad Remlī, a Shafiī savant, and also in the

book Iānat-ut-tālibīn alā-hall-i elfāz-i

Fath-il-muīn[1], that one cannot perform two rekats of those

prayers of fard namāz that contain four rekats, that two prayers of namāz

cannot be performed in the same time period before starting the journey or when

the journey is over. This fatwā is printed in the margins of the book Fatawā-i Kubrā[2].

Namāz cannot be performed in jamāat on different animals. After

stopping, it can be performed on the same individual mahmil, carriage or bus,

in jamāat, like performing it in a room.

It is written in Halabī-i kebīr:

As Shamsulaimma Halwānī said, if you start performing namāz while standing

towards the qibla on an animal and then the animal turns away from the qibla,

the namāz, if it is fard, will not be accepted. You must not remain deviated

from the direction of qibla as long as the duration of one rukn. [So is the

case when on a bus or train].

According to the Imāmayn, when on a sailing ship it is not permissible

to perform the fard namāz sitting without a very good excuse. Dizziness is a

good excuse. Imām-i azam said that even a dizzy person had better perform it

standing. If possible, it is better to get off the ship and perform the prayer

on land. A ship anchored out in the sea is like a sailing ship if it is rolling

badly with the wind. If it is rolling slightly, or if it is alongside the

shore, it is not permissible to perform the fard

---------------------------------

[1] Written by Abū Bakr Shatā 'rahmatullāhi ta'ālā 'alaih', (d.

1310).

[2] Written by Ibni Hajar-i-Mekkī 'rahmatullāhi ta'ālā 'alaih', (899 [1494 A.D.] - 974 [1566], Mekka.)

namāz sitting. If a ship has run aground, it is

always permissible to perform namāz standing on it. If the ship is not

stranded, majority of Islamic scholars say that it is not permissible to

perform the fard namāz on it if it is possible to get off. Such a ship is like

an animal. A stranded ship, [a bridge or a wharf built on masts in water or

fastened with chains to the bottom] is like a table or divan on land. When

beginning namāz on a sailing ship it is necessary to stand towards the qibla and,

if the ship turns, to turn towards the qibla during the namāz. For, turning

towards the qibla on a ship is like being in a room. It is not permissible for

a person who is able to make the rukū and the sajda to perform even the

supererogatory namāz by signs on a ship.

It is written in Marāq-il-falāh:

It is permissible to perform the supererogatory prayers in sitting position

even without an excuse. But the sunnat of morning prayer you must perform

standing. If you perform supererogatory prayers sitting you will be given only

half of the thawābs. When doing so you bend for the rukū and place your head

on the ground for the sajda. Or you stand up to make the rukū and then bend

into the rukū. He who cannot perform it standing performs it sitting. He bends

for the rukū, and places his head on the ground for the sajda. He who cannot

place his head on the ground for the sajda performs namāz by making signs.

It is written in Hidāya[1] and in Nihāya:[2] It is permissible to perform the fard namāz on a

docked ship. But it is better to get out and perform it on land. It is written

in Bahja:[3] When going from Istanbul to Üsküdar on a small

sailing ship, if the time of the early afternoon prayer is about to end, it is

permissible to perform early afternoon prayer sitting, since it is impossible

to get off the ship. When not travelling, a person cannot perform the early

afternoon prayer together with the late afternoon prayer by imitating the

Shāfiī Madhhab.

On the night of the Mirāj,[4] evening prayer was

arranged as

---------------------------------

[1] A book of Fiqh written by Burhān-ad-dīn Merghinānī

'rahmatullāhi 'alaih', (martyred in 593

[1197 A.D.] by the hordes of Dzengiz Khān.

[2] Written by Husayn bin 'Alī 'rahmatullāhi 'alaih'.

[3] Bahja-t-ul-fatāwā, by Abdullah Rūmī 'rahmatullāhi 'alaih',

(d. 1156 [1743 A.D.], Kanlżca,

Bosphorus.)

[4] Hadrat Muhammad's ascent to heaven. There is detailed information about Mi'rāj in the first fascicle of Endless Bliss and in Belief and Islam.

three rakats and the

other fard prayers as two rakats. A second commandment in the blessed city of

Medina increased all the five prayers, except morning and evening prayers, to

four rakats. In the fourth year of the Hegira these prayers were reduced again

to two rakats for a traveler. In the Hanafī Madhhab it is sinful for a

traveler to perform them as four rakats (Durr-ul-mukhtār).

If a musāfir performs the fard as four rakats, the last two rakats

become supererogatory prayers. But he becomes sinful because he has disobeyed

the commandment, he has omitted the takbīr of iftitāh (beginning) for the

supererogatory prayer, he has omitted the salām of the fard and because he has

mixed the supererogatory prayer with the fard. He may go to Hell if he does not

make tawba. A person who forgets and performs four rakats must make the

sajda-i sahw. If the imām who is musāfir performs four rakats by mistake, the

namāz of a settled person who has followed him becomes fāsid (it will not be accepted).

If he does not sit in the second rakat, his fard namāz will not be accepted.

If, before making the sajda of the third rakat, he intends to stay for fifteen

days in that city, he will have to perform that fard namāz as four rakats. But

it will be necessary for him to repeat the qiyām and the rukū of the third

rakat because he has performed those two (the qiyām and the rukū) as

supererogatory prayer. A worship performed as supererogatory cannot take the

place of a fard. [Hence it is understood that the supererogatory prayers or the

sunnats cannot take the place of those fard prayers that have been left to

qadā]. Please see the twentieth chapter.A musāfir says short

sūras. He makes the tesbīhs no less than three times. On his way, i.e. when he

is in trouble, he can omit the sunnats except the sunnat of morning prayer.

However, it is permissible to omit the sunnats with a good excuse. [Hence it is

understood that the sunnats can be performed with the intention of performing

the qadā of the omitted fard prayers].

If a person intends to go back before having gone a distance of three

days, he automatically goes out of the state of being a musāfir. He becomes

settled. If a person who has left the city with the intention of going a way of

three days enters his own city after having gone more or less than a three

days journey, or if he intends to stay for fifteen days at some other place,

he becomes settled again. If he intends to stay there less than fifteen days,

or if he stays there for years without intending to do so, he is a musāfir. If

a soldier in dār-ul-harb intends to stay at some place even for fifteen days,

he does not become settled.Also a

musāfir who intends to stay for fifteen days on a

ship out in the sea or on an uninhabited island does not become settled. A

sailor does not become settled even if his posessions, wife and children are on

the ship. A ship is not a home. Those who intend to stay for fifteen days

altogether in different places such as Mekka, Minā and Arafāt, do not become

settled. Those who are under orders, such as women, students, soldiers,

officers, workers, and children act not upon their own intentions, but upon

their husbands or mahram relatives, teachers, commanders, or employers

commands. If their commander intends to stay at some place for fifteen days,

they remain musāfir until they hear of the commanders intention. Upon knowing

the intention, they become settled. Soldiers who invade an enemy country or who

besiege a fortress from land or sea become musāfir even if they intend for

fifteen days. Those who go to an enemy country, but not for war, become musāfir

or settled, depending on their intention. A person who has just become a Muslim

in Dār-ul-harb is settled if he is not

under torture. Those who live in tents become settled when they intend to stay

in a desert for fifteen days. Others do not become settled in a desert.

He who sets out for a journey towards the end of the time of a certain

namāz performs two rakats of that namāz performs a namāz of two rakats if he

did not perform it (before setting out). He who arrives at his home towards the

end of a prayer time performs four rakats if he did not perform it (during the

journey).

The place where a person is settled or where he has settled his home is

called a Watan (home). There are three

kinds of watans in Hanafī Madhhab. The first one, Watan-i

aslī, ones real home, is the place where the person was born or got

married or where he established his home with the intention of living there

permanently. If he intends to leave the place years later or when something he

expects happens, he has not settled there even if he lives there for years. If

a person gets married at a place without intending to stay there even for

fifteen days, that place becomes his watan-i aslī. He becomes settled there.

When a person who has wives from two different cities goes to one of those

cities, it becomes his watan-i aslī. He becomes settled in those cities. If his

wife dies, that place is no longer his (real home), even if he has houses or

land there. If he goes to a place where he did not get married and intends to

establish his home there, the place becomes his real home. Even if the place

where the parents of a boy at the age of puberty live is at the same time the

place where

he was born, if he leaves the place and settles in

some other place where he intends never to leave, or if he gets married there,

that place becomes his real home. When he visits his parents, their residence

does not become the boys real home unless he intends to reestablish his home

there. His real home is where he got married or where he settled last. When

settling at a place, his former watan-i aslīs, where he settled before and

where he was born, become invalid, even if the distance between them is less

than three days or even if he did not set out with the intention of being

safarī. If a person who has left his real home in order to settle in another

place changes his way to settle at some other place, he performs namāz four

rakats while going through his first place. For he has not acquired a new home

yet. If he makes his wife settle in one place and then he himself settles in

another place, both places become his watan-i aslī. When a person enters his

watan-i aslī he becomes settled. He does not need to intend to stay there for

fifteen days.

The second watan is called Watan-i iqāmat,

transient home. A place where one intends to stay continuously for fifteen days

or more in Hanafī and for four days or more in Shāfiī and Mālikī, excluding

the days of arrival and departure, and then leave, is called a Transient home. If a person, while intending to

stay at a place for fifteen days, intends also to go to some other place and

then return there within these fifteen days, that place does not become his

transient home. If he intends to stay there at nights and at some other place

during the days, the former becomes his Watan-i iqāmat. If he intends to stay

at a place for years in order to receive an education or to do some job there

and then leave after finishing it, the place becomes his Watan-i iqāmat. If he

settled there with the intention of never leaving, it would become his Watan-i

aslī. Three things invalidate the watan-i iqāmat: When one goes to another

watan-i iqāmat the first watan-i iqāmat becomes invalid, even if one did not

set off with the intention of being safarī, even if the distance between both

places is less than three days way. Secondly, going to ones watan-i aslī

invalidates it. For example, if a person who follows Hanafī Madhhab stays in

the blessed city of Mekka for fifteen days and then goes to Minā and gets

married there, Minā becomes his watan-i aslī. The blessed city of Mekka

al-mukarrama leaves the state of being his watan-i iqāmat. The third cause is

to set out on a journey (with the intention of being

safarī). That is, if a person leaves his watan-i

iqāmat with the intention of going to a place of three days plus three nights

way, the first place is no longer his watan-i iqāmat. If he goes and comes back

with the intention of a shorter journey, his watan-i iqāmat does not become

invalid. If he leaves his watan-i iqāmat without an intention (for safar) but

at another place intends to go to a place that is three days away and then

enters his watan-i iqāmat again before having travelled for three days, his

being safarī becomes invalid, and he becomes settled. If he enters there after

having gone a distance of three days, even if he set out with the intention (of

safar), or if he never goes through his watan-i iqāmat, he does not become

settled. In the Shāfiī Madhhab, if a person (going on a safar) knows that the

business he is going to do there is going to take no less than four days, he

becomes muqīm (settled) as soon as he reaches his destination even if he does

not make niyyat. If he does not know well how long it will take, he becomes

settled eighteen days later.

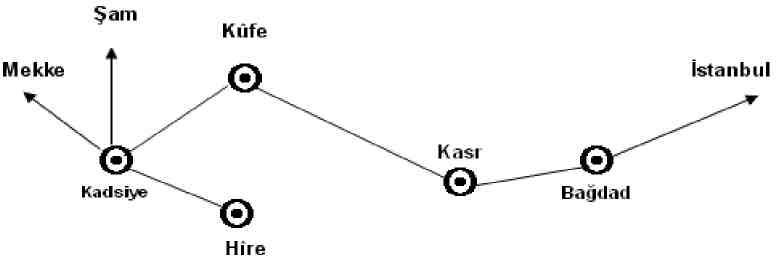

If two people who follow Hanafī Madhhab, one travelling from Istanbul

to Baghdad and the other from the blessed city of Mekka to Kūfa, both intend to

stay at their respective places for fifteen days and later leave those places,

which have now become their respective watan-i iqāmats, and then go to a place

called Qasr, neither of them becomes a traveller when arriving in Qasr. For the

place called Qasr is between Baghdad and Kūfa and is a two days way from both

places. If they intend to stay in Qasr for fifteen days, Baghdad and Kūfa are

no longer their watan-i iqāmats. For the place called Qasr has now become their

new watan-i iqāmat. If they go from Qasr to Kūfa fifteen days later, they do

not become safarī. If they leave Kūfa a day later and go to Baghdad through

Qasr, they never become safarī on their way because Qasr is the watan-i iqāmat

for both of them. When they leave there without intending for a journey of

three days and then come back, they do not become safarī. When they first left

Baghdad and Kūfe, if they intended for a way of four days, meeting in Qasr and

then going to Kūfa together and staying there one day and then leaving for

Baghdad, they would be safarī the entire time because they would have intended

for a journey of three days. The one from Istanbul would have walked that

entire distance. And when the one from the blessed city of Mekka set off on the

journey, Kūfa would have no longer been his watan-i iqāmat. Since the city of

Qasr is not their hometown, their going through it would not cause them to

become settled. If the one

from Istanbul, after staying in Kūfa for fifteen

days, left with the intention of going to Mekka and then returned to Kūfa for

some business before having gone a way of three days, he would not have become

settled. For, upon his leaving the city with the intention of going a three

days way, the city of Kūfa would have left the state of being his watan-i iqāmat.

Kūfa is south of Baghdad and Kerbelā.

The third kind of home, Watan-i suknā,

is the place where one has stopped, intended to stay less than fifteen days, or

where one has lived for years though one may have intended to leave there a day

after ones arrival. A safarī person must always perform two rakats of the

fard prayers in the watan-i suknā. If a person arriving in a city or a village

intends to stay there ten days and if after ten days he intends again to stay

there seven days longer, he does not become settled.

Being in ones watan-i iqāmat or watan-i suknā does not invalidate

ones watan-i aslī. Setting out for a journey does not invalidate ones watan-i

aslī, either. Being in a watan-i suknā does not invalidate ones watan-i

iqāmat. But it invalidates ones former watan-i suknā.

A safarī person does not become settled when he is in a watan-i suknā.

A person who is not safarī is settled in a place where he makes his

watan-i-suknā. If a person who has left his town in order to go to a village

that is not so far as a safar[1] from his town stays in

the village for less than fifteen days, the village becomes his watan-i suknā. He does not become safarī there.

He performs the fard prayers completely. Then, if he leaves the village without

intending for a safar and if he intends for a safar on the way before arriving

in his own town or in another watan-i suknā, he must perform two rakats of the

fard prayers on the way. If he enters the village he becomes settled. Not

having entered his watan-i aslī or another watan-i suknā, and having started

without the intention of a safar, his watan-i suknā does not become invalid. As

it is seen, invalidation of the watan-i suknā is similar to the invalidation of

the watan-i iqāmat. Ones being settled in the watan-i suknā requires that the

watan-i suknā be within a distance less than a safar [three days] from ones

watan-i aslī or watan-i iqāmat.

A person is going, say, from Kūfa to Qadsiya. The distance between them

is less than three days way. He leaves Qadsiya for

---------------------------------

[1] A journey that would take three days plus three nights by

walking.

Hira. Also the distance between these two is less

than a way of three days. Then he returns to Qadsiya before arriving in Hira.

He will pick up something he has forgotten and then go to Damascus. He does not

go through Kūfa. He must perform the fard namāz completely in Qadsiya because

when leaving there he did not intend to be a safarī, nor did he enter Hira;

hence, Qadsiya is still his watan. Hira is five kilometres southeast of Kūfa,

and Qadsiya is a little farther down south.

If a person sets off for a journey of three days way and stays at a

village less than fifteen days before having gone a way of three days but

leaves the village and then returns there again, he does not become settled.

This is because he was safarī when he first arrived there, too.

If a menstruating woman who does not have her husband or a mahram

relative with her sets off for a journey with the intention of a safar, this

intention is of no value. She does not become safarī at the place where she

stays before travelling for three more days after her menstruation is over.

It is written in the books Berīqa and Hadīqa: It is harām in the three Madhhabs for a free woman to go on a journey of three days alone or with other women or with her mahram relative who is not at the age of wisdom and puberty and who is not pious without her husband or one of her eternally mahram relatives to accompany her. In the Shāfiī Madhhab, women may go out for a hajj that is fard without any one of their mahram relatives with them. It is mekrūh for one man or two men to go on a safar (a three days journey). It is not mekrūh for three men. It is sunnat for four men to travel together and for them to choose one from among themselves to be the commander. The book Hindiyya, in its chapter about nafaqa, and the books Tahtāwī, Durr-ul-mukhtār and Durr-ul-munteqa, in the chapters dealing with hajj (pilgrimage), state: A woman can set off on a safar with a murāhiq, that is, her mahram relative who is twelve years old and who has almost reached the state of puberty.The book Qadīhān states: A woman can set off on a safar with a group of pious people. [It is permissible to act upon

these two judgements when there is a good excuse.]

The book Majalla, in its 986th article,

states: To complete the ages of nine and twelve is to enter the state of

puberty for girls and boys respectively. The extreme limit is fifteen for both

of them. When the age of fifteen is completed, they are said to have reached

the age of puberty. Those who have completed the ages of nine and twelve but

who have not experienced the state of puberty are called murāhiq.

Aggrieved I am, from Khudā I demand remedy for my distress,

Incapable I am, from true Forgiveness I demand favour and kindness.

With black face, sins teeming,

Ive always been disobedient,

From the Janāb-i Kibriyā I demand pardon and forgiveness.

Heartfelt resolved I am to keep

in the right path,

And so I demand a chance to attain His grace.

A diver I have been into the

ocean of Islamic dīn,

From ocean I demand pearls, corals at each dive into deepness.